SHORT SERVICE COMMISSION OFFICERS AND PENSION: NO STATUTORY ENTITLEMENT

Blog post description.

Short Service Commission Officers And Pension: No Statutory Entitlement

-Tanmay Kaushik*

INTRODUCTION

SSC (Short Service Commission) officers are appointed for a fixed, short-term tenure in the Indian Army, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard. Depending on branch and intake year, an SSC officer typically serves 5 years (extendable to 10) or 10 years (extendable to 14)[1]. Upon completing this tenure (without converting to Permanent Commission), SSC officers are released.[2] By contrast, Permanent Commission (PC) officers serve at least 20 years and qualify for pension under the Armed Forces pension rules.

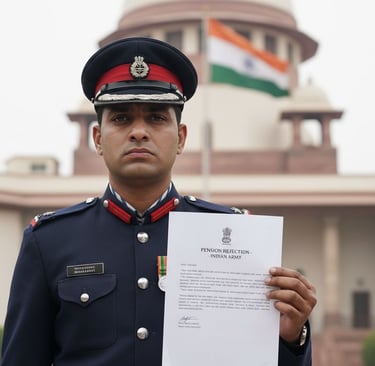

Despite performing identical duties and facing the same risks, SSC officers historically received no retiring pension. The only retirement benefit granted under service rules has been terminal gratuity (a lump sum), with pensions reserved for those completing the long service threshold[3][4]. A recent petition in the Supreme Court (filed by ~1,500 SSC officers) invokes Articles 14, 21 and 300A, seeking post retirement pension and provident fund benefits[5]. This paper argues that under current law SSC officers have no statutory entitlement to pension and that judicially imposing one would conflict with the legislative framework and precedents. We first examine the statutory/regulatory scheme, then review case law on SSC entitlements, and finally address the major counterarguments.

Statutory Framework

Definitions and Terms of SSC Service

Each service law (Army Act 1950, Navy Act 1957, Air Force Act 1950, Coast Guard Act 1978) distinguishes Permanent Commission from Short Service Commission. An SSC is a contractual commission for a fixed period. For example, an Army instruction (1996) formally replaced Women’s Emergency Commissions with SSC, fixing the maximum term at 14 years[6].

SSC appointments have explicitly limited tenure: originally 5–10 years (Army policy till 2005) later changed to 10+4 years.[7] The Armed Forces Acts do not guarantee any pension or permanent status to SSC holders; rather, SSCs are issued with the understanding that “on expiry of [their] contractual period… they will be released from service” with no claim to further service.[8]

SSC status is purely contractual. The Armed Forces Tribunal has stressed that an SSC officer’s “contract… is binding” and not subject to unilateral alteration.[9] Courts have held that once one accepts the SSC terms (“knowing fully well the terms”), one cannot later claim benefits beyond them.[10] In short, SSC service is not like open ended tenure; it is a known, finite engagement and all benefits must derive from statute or contract.[11]

Pension Regulations

1. Army Pension Regulations (PRA, Part I 2008)

The Pension Regulations for the Army (Part I, 2008) set eligibility at 20 years of qualifying service for officers (15 years for “late entrants”).[12] Regulation 34 explicitly provides: “The minimum period… required for earning a retiring pension shall be 20 years (15 years in the case of late entrants)”.[13] Likewise, Chapter VI (post Commission service) grants weightage only to Permanent and Emergency commissions (e.g. five year addition for regular officers)[14], critically, Short Service Commission officers are excluded from any weightage beyond their actual service.

Chapter 7 (“Emergency and Short Service Commissions”) contains no retiring pension at all. It provides that SSC officers are entitled to terminal gratuity (Reg.170) and, if invalided out or handicapped by service, to disability/invalid pension analogous to regular officers.[15] But there is no provision for ordinary retirement pension for an SSC officer completing his tenure. The sole benefit is gratuity (one half month’s pay per six months of service).[16] Hence, under Army rules a normal retiring pension is not even on the table for SSC personnel (they are not “entitled to pension” by the letter of the regulations).

2. Air Force and Navy Pension Regulations

The Air Force Pension Regulations (Part I, 1961) similarly require a minimum regular service of 15 years to earn a service pension.[17] The Navy Pension Regulations (1984, revised) likewise treat SSC officers differently. Chapter XII of the Navy regulations (for SSC officers) grants only terminal gratuity and disability pension; it contains no retiring pension clause for routine retirement.[18] For instance, Navy Regulation 12.1(a) fixes the terminal gratuity rate for SSC officers and notes that government may grant gratuity “at its discretion” on disciplinary release.[19] All disability/war pension provisions for SSC are explicitly tied to cases of invalidation or injury, mirroring the regular scheme (Chapter XII–XIV).[20] But no provision is made for ordinary pension at tenure end.

Coast Guard pension rules follow the same pattern (modeled on Navy). In sum, none of the statutory or regulatory pension schemes provides a retiring pension to an SSC officer completing the fixed term. The foundation of entitlement is absent. By contrast, Permanent Commission officers (and long serving JCOs/ORs) qualify by 20 (or 15) years under the Old Pension Scheme or New Pension Scheme (which explicitly exclude SSCs).[21] Under the Central Civil Services (Pension) Rules, regular civilian staff become pensionable after 10 years of service (or immediately for judicial/police postings); again, SSC officers are not covered by that statute. Legislative intent is clear: SSC service is too short to meet the pension service threshold, so only gratuity is provided.

Difference from Permanent and Civil Service

SSC officers are a distinct class from career officers. Permanent Commission (PC) officers, like other government servants, earn pension rights by law: Army/Navy/AF PCs under OPS get pension after 20 years (or less for early pension, with pro ration); civilian officials have similar rules (e.g. CCS (Pension) Rules).[22] SSC officers knowingly accepted a shorter career track. Equating them with permanent cadre ignores the rational basis for the distinction (short vs. long service; gratuitous vs. contractual terms). Likewise, SSCs resemble short term contractual employees in other sectors (who also lack entitlement to government pension unless specifically extended a scheme). The service laws treat SSCs as non pensionable, while PCs and long term service personnel are pensionable. This clear statutory classification underpins all judicial analysis below.

Case Law Analysis

Indian courts have addressed SSC benefits in several contexts. Crucially, no Supreme Court judgment holds that SSC officers have a statutory right to pension. By contrast, courts have emphasized that pension schemes are statutory and administration driven, and that classification differences will not automatically violate equality unless shown arbitrary. Key cases:

· Union of India v. Hariharan, (1997) 3 SCC 568: This case involved pay fixation and promotions in civilian services. The Supreme Court cautioned that matters of pay scales and benefits are primarily executive policy, and tribunals must be cautious before altering them. The Court observed that “matters relating to pay scales are to be heard by a bench including a judicial member” and that interfering with such scales absent “a clear case of hostile discrimination” is unjustified.[23] By analogy, alterations to pension rights likewise rest with the legislature/executive unless arbitrary discrimination is established. Hariharan underscores that courts will uphold governmental pension policies unless demonstrably capricious.[24]

· State of Punjab v. Boota Singh, (2000) 3 SCC 733: Boota Singh was a retirement benefit case under state rules, not military, but it illustrates the equality principle in pension contexts. The Supreme Court upheld classification between beneficiaries based on retirement date. It held that persons who retired under an old scheme cannot demand benefits granted later to retirees after a cut-off. Declining benefit changes for those who retired earlier was not “arbitrary” given policy and fiscal considerations.[25] The Court reasoned that specifying the cut off date for liberalized pension was justified, and retirees before that could not be equated with later retirees.[26] Boota Singh demonstrates that different terms of service (or retirement dates) can form a valid classification under Article 14. By parity, SSC officers (shorter service) constitute a different class from long service officers, and the rule excluding them from pension is a rational distinction, not forbidden discrimination.[27]

· Union of India v. P.K. Chaudhary, (2016) 4 SCC 236: This case (concerning social media restrictions on officers) included a clear statement on benefits and expectations. The Court held that “the mere reasonable or legitimate expectation” of a citizen does not by itself create “a distinct enforceable right” though failure to consider such expectation could render a policy decision arbitrary.[28] Applied here: an SSC officer’s belief that he “should” get pension (perhaps by analogy to PCs) is only an expectation, not a legal right. Without a statutory entitlement, one cannot transform that expectation into an enforceable claim. Chaudhary thus rebuffs the notion that SSCs have any vested pension right merely by virtue of service.

· Boota Singh and Hariharan together illustrate a broader judicial approach: insofar as SSC officers argue equal treatment or fundamental rights violations, the courts require a link to law. The state can differentiate SSCOs because (a) they serve fewer years and (b) the pension regulations explicitly set longer tenure for pension. If SSCOs contend this is arbitrary, they face the high burden (per Boota/Hariharan) of showing hostile discrimination. To date, no court has found such discrimination in the SSC context.

· Additional Precedents: Other authorities reinforce these principles. For instance, Deoki Nandan Prasad v. State of Bihar (1971) held that “pension is not a bounty payable at the pleasure of the Government, but…a valuable right vesting in a Government servant”.[29] This confirms pension’s status as property under Article 300A once law has granted it. But crucially, that case presumed an entitlement under existing rules. If no entitlement exists by statute, then there is no right to vindicate. Likewise, the Armed Forces Tribunal has noted that the SSC appointment is a binding contract,[30] the courts cannot rewrite that contract.

· Recent Developments: In April 2024, the Supreme Court granted a one time pensionary benefit to women SSC officers in Wg Cdr A.U. Tayyaba (Retd.) & Ors. v. UOI.[31] However, the Court explicitly did so by deeming these officers to have completed the 20 years required for pension.[32] In other words, the Court crafted an equitable remedy – not by recognizing a pre existing legal entitlement, but by treating them as if they had met the service threshold. The order did not alter the statutory requirement; it simply granted relief on a case by case basis. Thus, even this recent decision reinforces that the legal standard remains 20 years, and without special judicial remedy (as in Tayyaba), SSC officers do not meet it.

In summary, settled authority teaches that pension rights flow from statute and policy. SSC officers, by design, cannot meet the statutory pension criteria. Courts have consistently respected this scheme absent proof of invidious discrimination[33][34]. The absence of a pension provision in the very statutes and regulations governing SSC service is dispositive: no law = no pension right to enforce.

Doctrinal Context and Evolution

The doctrine of pension rights in India blends constitutional principles with service law. Historically, pension was regarded as a “compensation” for past service – an earned right, not mere grace.[35] Over time, the “right to livelihood” under Article 21 gave new weight to pension as a social safety measure, but always within the framework of legislative policy. The Supreme Court has never read Article 21 (or Article 14) to create a free standing entitlement to pension beyond what statutes allow.

To the contrary, in Deoki Nandan and related cases the Court emphasized that pension rules create the right; in Chaudhary it insisted that mere expectations cannot conjure up rights.[36][37]

Legislatively, the armed forces pension system has evolved to exclude short service appointees. From the early days of Women’s Emergency commissions through the establishment of SSC schemes (5–14 year terms), Parliament and the executive deliberately capped SSCOs’ tenure. Nothing in the debates or statutes suggested that these officers should later receive the same retirement benefits as long service cadres. If anything, a 2015 Ministry of Defence committee noted the plight of SSCOs and recommended a contributory NPS style scheme for them – a recommendation not implemented.[38] Thus, the policy has remained: SSC is a short-term scheme, and pension is reserved for full-service careers.

Counterarguments and Rebuttals

A. Article 14 (Equality): SSC officers argue that denying them pension while granting it to Permanent officers or civilian servants violates the constitutional guarantee of equality. The flaw in this argument is that all service members are not in an identical class. The law on Article 14 permits classification based on objective criteria. As Boota Singh makes clear, difference in retirement rules or dates justifies differential treatment.[39] SSC officers knew they were serving under a special scheme with its own terms. These terms – shorter tenure with gratuity – apply to all SSCs, irrespective of gender or cadre, so there is no invidious or arbitrary discrimination against an identifiable class. Moreover, as discussed, the pension rules explicitly tie retirement benefits to longer service. The classification (SSC vs PC) is rationally connected to the service length difference. Courts have upheld such classification (upholding cutoff dates, etc.) as constitutional.[40]

The appellants might claim that SSC vs PC is a “suspect” classification, but courts disagree. In service matters, the Supreme Court repeatedly holds that statutory service terms (even if harsh) do not offend Article 14 unless shown to be wholly arbitrary.[41][42] Without proof of bad faith or discrimination, a government policy (like denying pension to SSCOs) is beyond judicial re write. As Hariharan teaches, tribunals and courts must defer to policy on pay/pension unless a clear arbitrary element is proved.[43] Here, the policy goal of SSC (short term specialists) provides the reasonable basis for excluding pension – it is not random or capricious.

B. Article 21 (Right to Life/Livelihood): Petitioners invoke a right to “dignified living” and livelihood. However, Article 21 protects life and liberty; it does not create new welfare benefits not grounded in law. The Supreme Court has never interpreted Article 21 to impose an obligation on the state to give pension to a class not covered by law. Critically, even under Article 21, the state’s action must comply with law and reasonableness. Here the “law” (pension regulations) expressly requires more years than SSC officers serve.[44]

The 2024 The Print report notes that courts have observed “pension is not a bounty” and is treated as a right when law so provides.[45] But if the law itself precludes SSC officers, Article 21 does not override that. Indeed, to entertain a free floating right to pension under Article 21 would exceed the scope of the Constitution; that right is secured through Article 300A and statute, as discussed next.

C. Article 300A (Property): Petitioners may argue that pension (or expectation thereof) is a “property” right, and withholding it violates Article 300A. Here again, the key is whether pension is “property” for SSC officers. Under Article 300A, only rights recognized by law qualify as property. Since the statutes and regulations make SSC officers non pensionable, they have no entitlement in law. Without a legal pension right, there is no property interest to have been taken. The Supreme Court’s statement (Deoki Nandan) that pension is a right under 300A[46] is confined to persons lawfully due pension. If an SSC officer has no pension by law, the state has not “withheld” anything.

In short, Articles 14/21/300A arguments flounder on the threshold question of entitlement. Courts have uniformly held that pension is as guaranteed as the statute makes it. In Union of India v. Hariharan the Court rebuffed challenges to pay/pension rules by noting the power of the government to frame them (with legal remedy only if discrimination is shown).[47] The Constitution protects pensions already vested, but it does not compel creation of new pensions.

D. Comparison with Civil/Contract Employees: There is no general entitlement to pension for contractual or short term government employees. Even in civil services, one needs 10–20 years as per CCS (Pension) Rules. Similarly, many contractual jobs yield only provident fund or gratuity, not pension. SSC officers are akin to armed forces contract employees; if mere equal responsibility conferred a pension right, every temporary govt employee could claim one. The law clearly distinguishes career from temporary service. SSC officers willingly joined on known terms; absent fraud or rights violation, courts will not rewrite that bargain under guise of equality.

Conclusion

The weight of statutory text and authority is conclusive: SSC officers have no legal right to pension. The Army, Navy, Air Force and Coast Guard pension rules uniformly set minimum service well above the SSC tenure. Courts have consistently respected the armed forces policy choices on pay and pensions, intervening only to guard against proven arbitrariness.[48][49] The petitioners’ equality and livelihood claims, while sympathetic, must give way to the clear legislative scheme. Only Parliament or the executive (subject to budget and policy considerations) can extend pension benefits to SSCs; the judiciary lacks the power to override the statutes that explicitly exclude them. In short, SSC service is contractual and conclusively defined as non-pensionable, and the jurisprudence strongly upholds that distinction.[50]

Sources: Statutes and pension regulations (Army Act 1950, Navy/AF Acts, Army Pension Regs 2008, Navy and Air Force Pension Regs), Supreme Court and Tribunal judgments, and official policy documents have been reviewed to support these conclusions.[51]

REFERENCES

* Student of B.B.A LL.B. (H), 5th Semester at Vivekananda School of Law and Legal Studies (VSLLS), VIPS, Delhi

[1] Supra note 2

[2] The Secretary, Ministry of Defence vs. Babita Puniya and Ors. (17.02.2020 SC) Link

[3] Supra note 1

[4] Navy Pension Regulation Link

[5] Mandhani, A. (2024, May 10). SC to take up over 400 SSC officers’ plea seeking post retirement benefits , ‘breach of Article 14'. ThePrint. Link

[6] Supra note 5.

[7] Supra note 2.

[8] Supra note 5.

[9] Supra note 2.

[10] M/S. Ambuja Cements Ltd. v. State Of Himachal Pradesh And Others Link

[11] Supra note 2.

[12] Supra note 1

[13] Id

[14] Id

[15] Id

[16] Id

[17] Supra note 3

[18] Supra note7

[19] Id

[20] Id

[21] Supra note 8

[22] Id

[23] Bharat Pensioners Samaj. (n.d.). Bharat Pensioners Samaj. Link

[24] Id

[25] State of Punjab v. Boota Singh Link

[26] Id

[27] Id

[28] Supra note 13

[29] Effect of The Pensions Act, 1871 On the Right to Sue for Pensions of Retired Members of the Public Services. (n.d.). AdvocateKhoj. Link

[30] Supra note 2

[31] Kaur, T. (2024, April 22). Supreme Court Clarifies Its Previous Order On Pensionary Benefits For Short Service Commission Officers. Verdictum. Link

[32] Id

[33] Supra note 29

[34] Supra note 28

[35] Supra note 32.

[36] Id.

[37] Supra note 13.

[38] Supra note 8.

[39] Supra note 28.

[40] Id.

[41] Id.

[42] Supra note 26.

[43] Id.

[44] Supra note 1

[45] Supra note 8

[46] Supra note 32

[47] Supra note 26

[48] Id.

[49] Supra note 28.

[50] Supra note 13.

[51] Id.